If you’ve ever heard Canada’s current prime minister, Justin Trudeau, speak French and English, you know he speaks them extremely well. He comes across as articulate and eloquent yet personable in both languages. This is what I call high-performing bilingualism, and it can hardly get better than that. In this post I want to look briefly at how Mr Trudeau acquired these language skills. And then I want to discuss the language learning challenges of would-be prime ministers and adult learners in general.

Canadian institutional bilingualism

Canada has two official languages. This does not mean Canada is a bilingual country in the sense that most Canadians speak two languages or that both languages are spoken everywhere. Far from it. What we have is really a form of institutional bilingualism whereby the federal government and some provincial governments are obliged to provide services in both languages where reasonably possible.

The great majority of the Canada’s French-speaking population is concentrated in the province of Québec, also home to a sizeable English-speaking minority.

Another province, New Brunswick, has a substantial French-speaking population and has declared itself officially bilingual. All the other provinces are predominantly English-speaking with small French-speaking minorities.

Given the massive exposure to English-speaking culture and the North American context, it is not surprising to observe that the most bilingual Canadians have always tended to be native French-speakers with good skills in English. This does not mean that all French-speakers also speak English. But in certain fields such as science, business, sports, politics and entertainment, knowledge of English is something of a necessity.

On the other hand, English-speaking Canadians have had little real need to speak French, especially since so many French-speakers had good English skills. But the situation has changed considerably in the last 50 years because of three important developments that took place between 1969 and 1977.

Three factors changing Canadian bilingualism

The first major event was the adoption of the Official Languages Act in 1969 and its amendment in in 1988. The basic principle of the law is that the federal government must provide all services in both languages where necessary. The application of the law is supervised by the Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages.

Probably the biggest impact of this law was the requirement of bilingualism for many jobs with the federal government. A very large number of positions have designated levels of certified second language skills. Employees in these bilingual jobs currently receive a language bonus of $800 CAD a year. That should be motivation enough to learn French.

Chronologically, the second major development was the spread of French immersion education programs throughout all of English-speaking Canada. The original experiment took place in a suburb of Montreal in 1965, and French immersion programs started to spread quickly in the 70’s.

French immersion programs became and remain immensely popular because parents immediately saw the advantages of introducing French to their children at an early age and also realized the very tangible advantages of bilingualism in the Canadian context.

The third important event was the adoption in 1977 by the province of Quebec of Bill 101 known as the Charter of the French Language. This legislation made French the official language of the province and has had a huge impact on the language of work, education, public signage, and communication between businesses, customers and government.

The bilingualism of Canadian prime ministers

All these developments, and particularly the Official Languages Act, have had an important impact on the language requirements for politicians at the federal level. In today’s Canada, the prime minister and high-level officials are expected to be able to communicate with Canadians in both languages. But this has not always been the case.

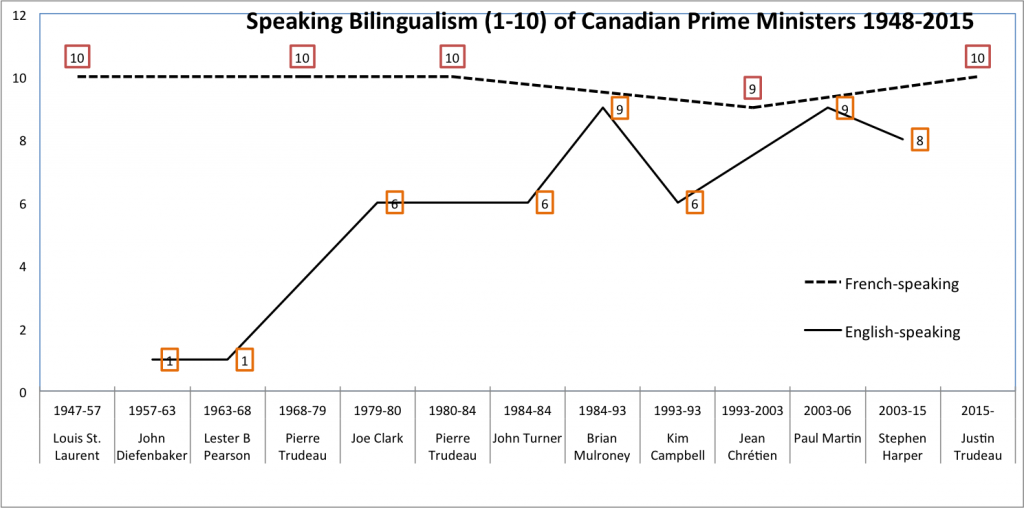

I’ve concocted a graph of the estimated speaking language skills of Canada’s prime ministers since 1948. Using a scale of 1 to 10 with 1 being the barest minimum of second language skills and 10 native-like skills, I looked at historical records to estimate the second-language speaking ability of recent Canadian prime ministers.

We see that the French-speaking prime ministers have always been pretty much perfectly bilingual. No surprise there.

What is quite striking is the evolution of the French speaking skills of English-speaking prime ministers. By the end of the 1970’s, it had become clear that the position of prime minister required proficient bilingualism.

What is true for the prime minister is also true of course for leaders of the various political parties. In addition, cabinet ministers and high-level officials in any sort of pan-Canadian organizations also require some level of bilingualism, the higher the better.

How do prime ministers become bilingual?

I believe there are basically two factors in the development of of high-performing bilingualism:

- Start young, preferably before the age of 13 -14. This is key for accent and fluency.

- Attend school, especially university, in the second language. This is key for vocabulary and grammar in formal contexts.

Justin Trudeau, a case in point

The language learning history of the current prime minister, Justin Trudeau, is arguably a textbook example of how one becomes perfectly bilingual in Canada. First of all, it certainly helped that his father was the 15th prime minister of Canada for 15 years and himself very bilingual. As a matter of fact, Trudeau the father was instrumental in the adoption of the Official Languages act.

Justin Trudeau’s mother, Margaret Joan Trudeau née Sinclair, is English-speaking. We can assume that Justin was brought up bilingually at home, probably speaking English to his mother and French to his father.

As for his schooling, it is a mix of French-speaking and English-speaking institutions. His first years were in a French-immersion program in an English-speaking public or state school in Ottawa, the nation’s capital. Then a year at the exclusive Lycée Claudel d’Ottawa. After moving to Montreal, he attended the alma mater of his father, the private Collège Jean-de-Brébeuf.

At the university level he has degrees from English-language institutions, McGill University and the University of British Columbia. He also spent a year studying engineering in French at the École Polytechnique in Montreal.

With this combination of bilingualism at home plus formal education in both languages, the impressive speaking results we see today were guaranteed.

Two bilingual English-speaking prime ministers

Looking at the chart of the language skills of the English-speaking prime ministers, you will notice that two of them have excellent French-language skills. Let’s look at their background.

Of the English-speaking prime ministers, the one with the most impressive second-language skills is Brian Mulroney. Wikipedia tells us that Mulroney grew up in Baie-Comeau, a town that is currently over 98% French-speaking. It would seem that Mulroney grew up bilingual. It was probably something like English at home and French outside.

All his formal education was in English, except – and a very important except – for four years of law at Université Laval in Quebec City.

The other prime minister with great French skills was Paul Martin who grew up in Ontario. The Great Canadian Encyclopedia tells us that: “In Ottawa the younger Martin was educated at a French elementary and bilingual high school. In 1962, he graduated with an Honours degree in philosophy from St Michael’s College at the University of Toronto. In 1965, he graduated from University of Toronto law school and was called to the Ontario bar the next year.”

Making the other English-speaking prime ministers bilingual

What interests me most is the English-speaking prime ministers – and adult learners in general – who did not have the benefit of childhood bilingualism and schooling in the second language.

First of all, I want to say that all recent English-speaking prime ministers have certainly made a very serious effort to learn French. The results are actually quite good, but as we see in the graph above, their level of proficiency does not come close to that of the group of true bilinguals.

How did they learn French? I can only assume that they had access to the best private instruction that money could buy. Not from me, but I should add that I did sell a large batch of my language calendars to the federal government.

The general observation I want to make here is that if you did not start quite young and go to school in French, your chances of becoming a high-level bilingual are quite remote. Of course, this is where I come in. I believe one can become quite proficient with the right tools and learning strategies.

The most difficult thing to acquire at an adult age is native-like accent. Unless you are an actor trained in dialect imitation, you will never sound like a native. But don’t despair. As I have written here, I also believe that some accent is actually not a bad thing when combined with great grammar and vocabulary. People will really admire your language skills all the more when they see that this is a foreign language for you.

A look towards future bilingualism

Two quick observations. First of all, I believe French immersion education in English-speaking Canada is certainly having an excellent influence in laying the foundation for adult bilingualism. This is something that I see all the time in my workshops. When I meet English-speaking Canadians with good accent and fluency, inevitably they have spent some time in French immersion. Early exposure does work wonders.

My other observation is the rise of English-speaking bilinguals from Quebec. Like their French-speaking counterparts with English, the native English-speakers growing up in Quebec are learning French by massive exposure and by schooling in French. In the provincial Quebec governments there have been a number of striking examples of English-speaking ministers with excellent French.

All this augurs well for future prime ministers and bilingualism in general. Yet there are would-be prime ministers and adults who face the challenge of learning French for professional purposes. It’s not easy and the stakes are high, as I’ll study in the part 2 of this post.

Related Posts

1. How important is accent?

Stanley Aléong is a polyglot, author, musician, language coach in French, English and Spanish, language workshop facilitator and organizer of French-English conversation meetups in Montreal, Canada. He likes to share his passion for languages and believes that anybody can learn to speak a foreign language well with the right methods and tools. He has also invented a cool visual learning tool called the Essential French Wall Chart Calendar. Reach him at info@fluentfrenchnow.com.